Understanding Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS): From Pathophysiology to Clinical Management

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) is one of the most common causes of lateral hip pain seen in clinical practice.

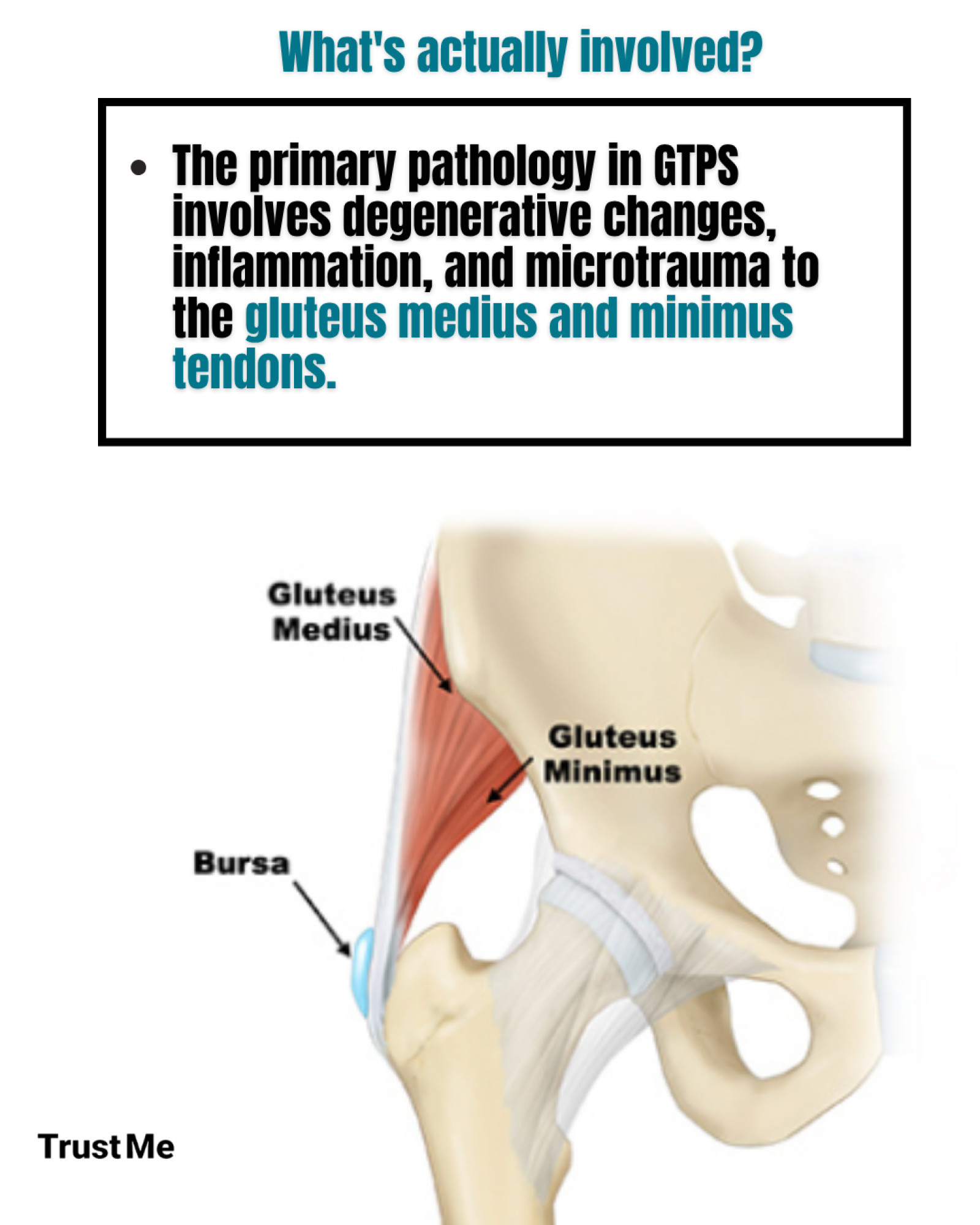

Once thought to be primarily “bursitis,” research now shows that GTPS involves much more than inflammation—it’s often a tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons, sometimes with associated bursal irritation.

If you want to learn more about this topic, you can watch Rachael McMillan's lecture here:

What Exactly Is GTPS?

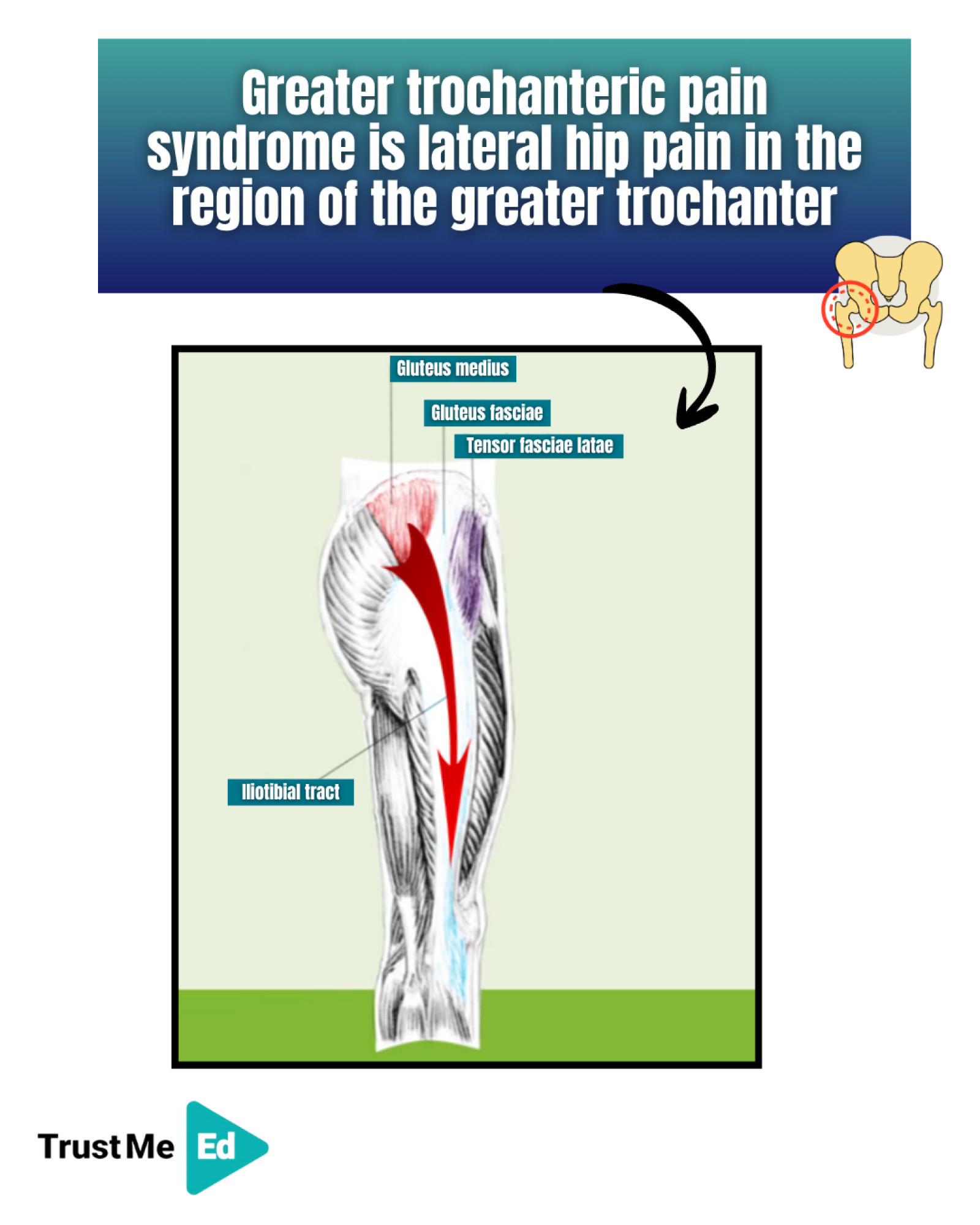

GTPS refers to pain in the region of the greater trochanter, typically due to compression and overload of the gluteal tendons where they attach to the lateral hip.

Historically called “trochanteric bursitis,” this term is now outdated, as isolated bursal pathology is rare. Instead, tendon pathology—especially of the gluteus medius and minimus—is the main driver.

Who Gets GTPS?

While GTPS can affect anyone, it’s three times more common in women than in men, particularly in postmenopausal women.

The likely reason? Declining estrogen levels after menopause negatively affect tendon health—reducing collagen synthesis, fibroblast activity, and overall tendon healing capacity.

Additional risk factors include:

• Increased age

• High body mass index (BMI)

• Genetic predisposition

• Corticosteroid use

• Sudden or excessive load changes

• Reduced female sex hormones

• Certain antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones)

Understanding Tendon Pathology vs. Tendinopathy

Tendon pathology refers to structural changes within the tendon—disorganized collagen, increased ground substance, and neovascularization.

However, tendinopathy is a clinical diagnosis—pain, loss of function, and reduced tolerance to load.

Importantly, tendon pathology doesn’t always mean pain, and imaging findings often don’t correlate with symptoms.

The Role of Load and Compression

Tendons thrive on mechanical load—but too much or too little can be harmful.

• Overload → microtrauma and tendon irritation

• Underload → weakened tendon structure

• Sudden load changes → poor tendon adaptation

In GTPS, the gluteal tendons face both tensile and compressive stress, especially as they wrap around the greater trochanter.

Compression—for instance, from lying on one side, crossing legs, or hip adduction—is a key aggravating factor.

Structural factors like a low femoral neck-shaft angle (coxa vara) or a wide greater trochanter increase compression and may predispose individuals to GTPS.

Clinical Assessment: What to Look For

A thorough subjective assessment is essential.

Key Questions:

• Where exactly is the pain?

• Any recent changes in load or activity (new exercise, long drives, increased walking)?

• Pain with lying on the side, sit-to-stand, stairs, or walking on slopes?

• Is it easy to put on shoes and socks? (If difficult, think joint pathology like OA.)

Pain Patterns:

Pain is typically felt over the lateral hip, but may radiate down to the thigh or even the ankle due to shared nerve supply (L5–S2).

Clinical Testing

No single test confirms GTPS—clinicians should use a battery of tests.

The Ganderton et al. (2017) study highlights four useful ones:

1. Resisted External De-rotation Test

2. FABER test

3. Resisted hip abduction

4. Palpation of the greater trochanter

These help reproduce pain linked to gluteal tendon compression or tension.

Management: Evidence-Based Approach

1. Exercise Therapy

High-quality research consistently shows exercise provides long-term benefits in GTPS.

The goal: improve tendon load tolerance, restore function, and reduce pain.

Key principles:

• Gradual, progressive loading of the gluteal tendons

• Avoid compressive positions (e.g., side-lying, crossing legs)

• Focus on hip abductor strengthening and movement control

2. Education

Patient understanding is critical. Educate on:

• Avoiding hip adduction postures

• Managing load and rest periods

• Importance of consistency over intensity

3. Hormonal Considerations

In postmenopausal women, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) may enhance outcomes.

A 2022 RCT by Cowan (McMillan) et al. showed that MHT combined with exercise and education improved outcomes more than exercise and education alone—particularly in women with BMI < 25.

Key Takeaways

• GTPS is not just bursitis—it’s primarily a gluteal tendinopathy.

• Most common in postmenopausal women, influenced by hormonal changes and biomechanics.

• Compression, not just overload, is a major driver of pain.

• Diagnosis is clinical, not imaging-based.

• Exercise + Education is the gold standard for long-term management.

• Hormone therapy may enhance recovery in select postmenopausal women.

If you want to learn more about this topic, you can watch Rachael McMillan's lecture here:

Source:

1. From the lecture ‘Navigating lateral hip pain in clinic’ by Dr. Rachael McMillan